'I Me Mine' and the curse of personal branding

Future Work/Life is a weekly newsletter that casts a positive eye to the future. I bring you interesting stories and articles, analyse industry trends and offer tips on designing a better work/life. If you enjoy reading it, please SUBSCRIBE HERE, and share it!

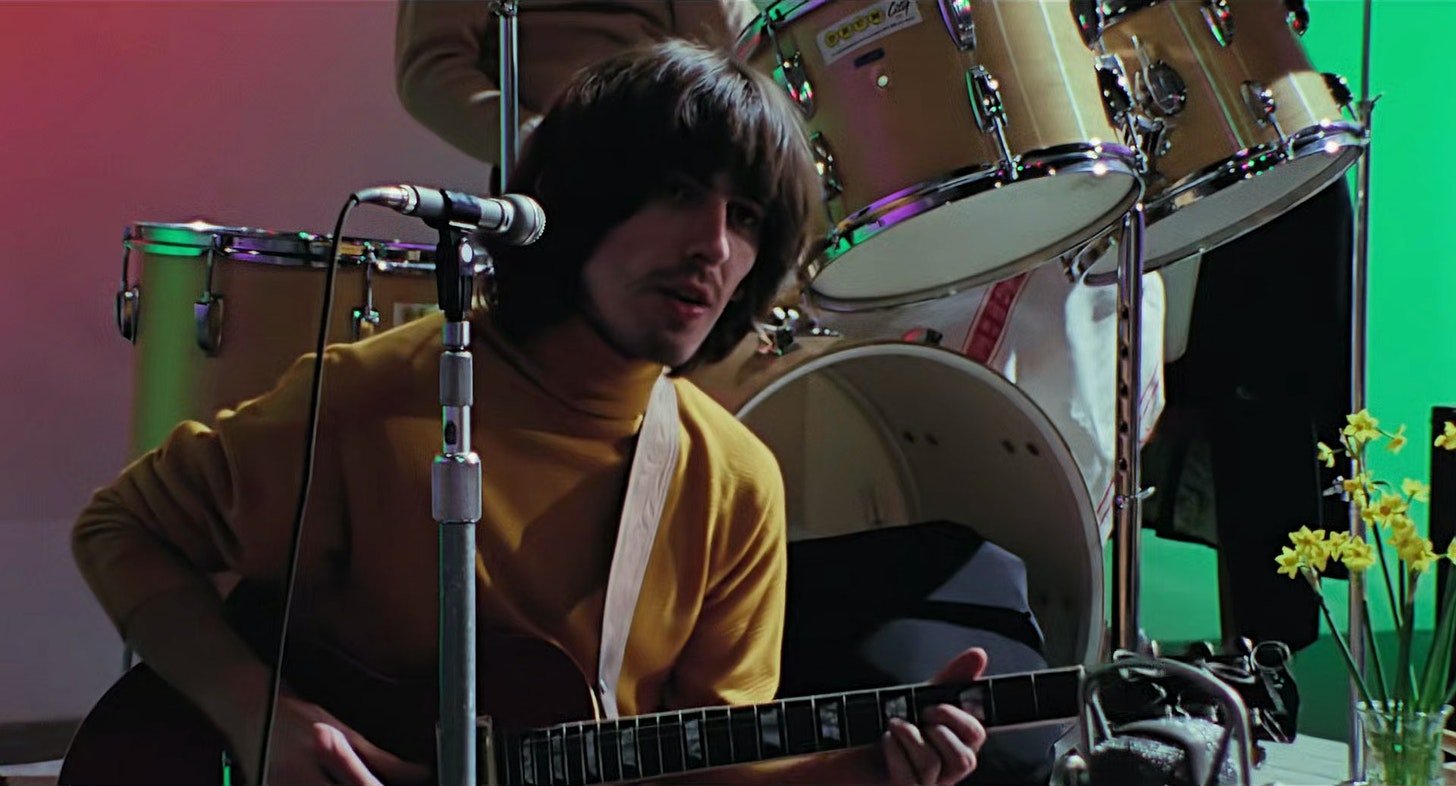

When The Beatles began recording Let It Be in 1969, the band was hanging together by a thread. It's hardly surprising that six years after 'Beatlemania' catapulted them into superstardom, the pressure had taken its toll.

Guitarist George Harrison, still only 26, wrote I Me Mine during the recording sessions. While later he explained that the song was more of a reflection on revelations he'd had about his ego while on LSD, its title encapsulated the mood around the band perfectly - perceived self-interest and self-importance, which endangered the collective magic that had always been present within this high performing team.

However, when it came to it, they were able to put their egos to one side, all understanding their roles in helping to achieve a shared objective - creating music that their fans loved.

I thought about this story after chatting to Christopher Lochhead on the podcast this week. Christopher, highlighting some of modern business's most troublesome ills, told me:

"Personal branding is another source of intergalactic bullshit...The most legendary people become known for a niche or category they own, and the stupidest thing about 'hustle' is it perpetuates the myth that you and I make ourselves successful. We don't make ourselves successful. Other people do."

The problem with personal branding is that it's all 'I Me Mine". It's become shorthand for making sure people can't miss you and for constantly ‘putting yourself out there’. Unfortunately, in most cases, the advice also loses sight of why you're doing it in the first place.

What value are you generating for the people reading, watching or listening to what you're saying?

Are you creating the equivalent of Let It Be, or are you more interested in receiving some easy 'likes' and virtual 'pats on the back’?

Remember, "we don't make ourselves successful. Other people do."

As for the idea we should 'always be hustling', it's easy to project the appearance of hyper-productivity to others. None of this is of any use, though, if you're not creating anything of value to yourself and, most importantly, others. These aren't new phenomena either. They've existed for millennia. Stoic philosopher, Seneca's described what we'd call 'the hustle' as 'busy idleness':

"All this dashing about that a great many people indulge in, always giving the impression of being busy."

Whether a Roman, a millennial, a boomer, or a zoomer, it's all too easy to get carried away by the productivity and self-improvement trends of the day. Stopping to get some perspective on the results of all that 'dashing about, on the other hand, is far trickier.

Psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm distinguished genuine productivity, which requires careful thought and intentionality, to the more frenetic and scattered approach that typifies our modern definition - being active does not mean being busy but rather:

"It means to renew oneself, to grow, to flow out, to love, to transcend the prison of one's isolated ego, to be interested…to give."

Another ancient philosopher, Aristotle, advocated the concept of eudaimonia, or flourishing, which aligns neatly with Fromm's thinking - being active means using our time and energy to grow and become a better person who gives more to others rather than takes.

Christopher Lochhead talks about the dangerous spread of 'Me Disease', and it isn't just that pursuing 'the hustle' or 'building your brand' wastes time. Worse than that, comparing yourself to others - and, in particular, a contrived social media version of others rather than the real thing - is bad for your mental health.

What’s more, constantly focusing on yourself can, contrarily, be detrimental to personal growth. The Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) is a part of your brain that fires when focusing only on ourselves and our perspective. Just as there are neurobiological triggers for entering flow state, there are also blockers. Guess which part reduces the chances of getting into the zone? That's right, your PCC. 'Me Disease' is a neurobiological impediment to high performance.

If you're concerned that you've been infected, take time to pause, step back and consider why you're doing what you're doing. As with any aspect of your work, an easy starting point is to focus on the problem you're looking to solve or the opportunity you're creating for others. If that work involves posting insights or sharing advice on social media, that's fine, but the simple rule should be – why should someone spend their their time consuming it? What's in it for them?

And if you want something to compare yourself against, how about yourself - benchmark your health, creativity, or career success in terms of the progress you make in your work/life.

Author Annie Dillard once said that "how we spend our days is how we spend our lives," so for the sake of yourself and everyone else, please spend your day focusing on stuff that matters. Less I Me Mine, more You Your Yours and We Us Ours…or something like that.

Have a great week,

Ollie

Any Other Business:

Great news! As MIT Sloan Management Review reports, ‘a large-scale study found that well-being predicts outstanding job performance.’

If you want to dig deeper into ‘how to engage well-being when designing high performing organisations and teams’, make sure you read this new whitepaper by the Health & Happiness Foundation. As authors, CEO (and FWL reader), Catalina Cernica, and researcher, Stine Derdau Sorensen, write:

“Your company has probably engaged with an agenda of improving employee well-being, at least in the last two years. This white paper will help you mitigate the risk of implementing superficial, shortterm solutions and give you a better understanding of what well-being at work really is and how companies can better design well-being strategies to improve business performance.”

This New York Times Magazine article describes why ‘when 25 million people leave their jobs, it’s about more than just burnout.’ Instead, it’s a reflection of an emerging ‘Age of Anti-Ambition’.

“It is in the air, this anti-ambition. These days, it’s easy to go viral by appealing to a generally presumed lethargy…“Sex is great, but have you ever quit a job that was ruining your mental health?” went one tweet, which has more than 300,000 likes. Or: “I hope this email doesn’t find you. I hope you’ve escaped, that you’re free.” (168,000 likes.) If the tight labor market is giving low-wage workers a taste of upward mobility, a lot of office workers (or “office,” these days) seem to be thinking about our jobs more like the way many working-class people have forever. As just a job, a paycheck to take care of the bills! Not the sum total of us, not an identity.”

A survey of 1,200 by The Times shows that many people in middle-management roles are feeling the strain from the huge upheaval in working practices brought about by the pandemic:

43 per cent of those surveyed said that hybrid working had made it harder to manage their teams, while 40 per cent said that it had made no difference, leaving only 17 per cent to say that things had improved. More than half said that their ability to build meaningful relationships with the members of their team had declined, while 69 per cent said that inducting new recruits was more difficult.

Reality is starting to bite for commercial real estate owners and this Economist article measures ‘The true cost of empty offices’.